Maurice Vachon, an amateur wrestling prodigy, vaunted street fighter, worldwide pro wrestling superstar and cultural icon in parts of Canada, passed away in his sleep on 11/21 at his home in Omaha, at the age of 84.

Vachon was a household name in many provinces in Canada, most notably Quebec and Manitoba, and his death was carried on the front page of a number of newspapers all over the country. Coverage of his death far exceeded similar coverage of recent deaths of Canadian Hall of Famers and legends like Hans Schmidt in 2013, and Gene Kiniski and Edouard Carpentier in 2010.

“They knew Mad Dog Vachon more than anybody,” said Gino Brito, a Montreal wrestling fixture as a wrestler and promoter, whose father, Jack Britton, was also a longtime promoter. “The difference is, everyone knew Maurice Vachon outside of wrestling. He was on TV, on the French station, his commercials for LaBatt beer were on television a lot, and he was a character on another television show, that’s how he got to be known by everyone. And then when he lost his leg, it was a big deal when Prime Minister (Brian) Mulroney flew him here.”

Most historians would say that Yvon Robert, a star in the 30s, 40s and early 50s, was Quebec’s all-time biggest wrestling star. Carpentier would be the second biggest, with Vachon, Killer Kowalski and Johnny Rougeau following. But Vachon was the best known mainstream by this generation, and he was undoubtedly the Quebec native who was the biggest star worldwide. Mad Dog Vachon would be one of the five biggest legends in the history of the American Wrestling Association. His mainstream fame is why the recently published authoritative history of Montreal wrestling, “Mad Dogs, Midgets and Screw Jobs,” by Pat Laprade and Bertrand Hebert, from the start, according to Laprade, had to have Mad Dog somewhere in the title. A panel of Montreal wrestling experts in the book ranked him behind only Robert as the greatest wrestler ever to come from Quebec (Carpentier and Henri DeGlane were both from France).

Brito noted that from the reaction of his death as compared with that of Carpentier, it’s now clear Vachon was the area’s most well known star.

The reaction included comments from some o the country’s best known political figures. Stephen Harper, the current Prime Minister, Thomas Mulcair, the national leader of the Opposition, and Jean-Marc Fournier, the leader of the Opposition in Quebec made public comments about Vachon after his death.

“When I think of Mad Dog Vachon, I relive some great moments at Paul Suave Center with the Rougeau brothers, LeDuc brothers, some legendary bouts with Edouard Carpentier, Gilles `The Fish’ Poisson and Michel `Justice’ DuBois (who later became Alexis Smirnoff), etc.” wrote Montreal mayor Denis Coderre.

Lucien Bouchard, the former premiere of Quebec, also noted that he remembered Vachon from going to matches in his hometown of Chicoutimi.

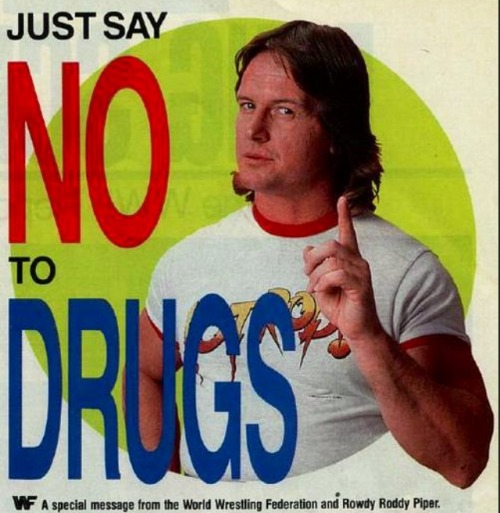

In all, Vachon was among pro wrestling’s all-time most memorable characters, and greatest promo men. It was once said by Ric Flair, who grew up watching Vachon as AWA champion and the top heel rival of Verne Gagne and The Crusher in the 60s, that you don’t know wrestling unless you’ve seen a Mad Dog Vachon interview. A member of every significant pro wrestling Hall of Fame, Vachon was listed in the book, “The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels,” as the fourth greatest heel in pro wrestling history, behind only Buddy Rogers, Gorgeous George and The Sheik.

With his shaved head, menacing scowl missing several teeth, goatee and unique guttural voice, he was both unmistakable and as memorable as they come. Although billed at 5-foot-9, Vachon was really only 5-foot-6 ½ and in his prime, maybe 200 pounds, although he got heavier and paunchier as he got older. But few would argue he was among the most fearsome and intimidating wrestlers of the last 60 years. And as a street fighter, everyone knew he was the living embodiment of the Tasmanian Devil.

Billy Robinson, who never even came across Mad Dog until Vachon was long past his prime, when asked about wrestlers from his generation who could have been MMA stars, always mentions Vachon first. Robinson said that he had no doubt that if UFC was around during the 50s and 60s that Vachon would have been world middleweight champion.

“I spent my whole life trying to get people to hate me. I failed miserably,” Vachon said in 1987, when he received 4,000 letters from people around the world after he was hit by a car while jogging and nearly being killed. The accident caused him to have much of his right leg amputated. He used an artificial leg, which Kevin Nash took off him and both he and opponent Shawn Michaels used it as a weapon in their 1996 WWF PPV match.

Vachon was born September 14, 1929, in Velle Emard, a section of Montreal, the son of a well known police officer, Ferdinand Vachon, who patrolled St. Lawrence Blvd. He was one of 13 children, the smallest of all the boys in the family, but, as brother Paul, who was 6-foot-2 ½ and nearly 300 pounds, would say, by far the toughest.

Even as a kid, he was always getting into fights.

“I was coming home from school with blood on my shirt quite often, and my father wanted to know why,” he would say. “I told him guys were shouting, `Vachon cochon,’ (the French word for domestic pig that rhymed with his last name) at me and I had to fight.”

His father didn’t seem as concerned about his son’s temper, and would only ask him after fights, “Did you win?”

As long as he said, “Yes,” everything was good.

At the age of 13, he once beat up the father of one of his school classmates. Needless to say, he didn’t last long in school.

His father, realizing his son’s temper, brought Maurice and two of his brothers to the YMCA in Verdun to train as a boxer, but he was taken under the wing of a coach who told him since he was more into fighting than boxing, that he should specialize in wrestling.

“He said in boxing, you get punches to the head and you can get punch drunk. He said in wrestling, you learn how to put guys down without being hit in the head.”

Vachon quit school at the age of 13, and lived for the sport of amateur wrestling, training under Frank Saxon, the one-time Canadian national team coach, who had previously coached the legendary Earl McCready. Vachon first won the city championship in Montreal and followed winning the provincial championship. He was a prodigy in the sport. He and his best friend and training partner, Fernand Payette, quickly became Eastern Canada’s two toughest amateurs. In 1947, before his 18th birthday, he won the Canadian freestyle national championship. The next year, he earned a spot on the 1948 Olympic team.

Competing at 174 pounds, he went to London as an 18-year-old, written up as “the baby of the Olympic team” in Montreal newspaper reports at the time. He was several years younger than anyone in his weight class. He ended up placing seventh. He first pinned Keshav Roy of India in 54 seconds. He next faced Adil Candemir, a 31-year-old from Turkey, losing a match that was tied after overtime and the three judges ruled against him in a very controversial split decision. The Canadian team protested stating that under any interpretation of Olympic wrestling rules he should have been ruled the winner. But the decision was upheld. He was then knocked out of the top tier, losing to Paavo Sapponen of Finland via unanimous judges decision.

Payette, who was seven years older than Maurice, competed at 191 pounds, and placed fourth in the competition won by Henry Wittenberg, one of the best U.S. wrestlers in history. While they never wrestled in that tournament, Payette finished ahead of seventh placed Karl Istaz of Belgium, who later became a pro wrestling legend as Karl Gotch. Also in London for those Olympics, as an alternate for Wittenberg, was LaVerne Gagne of Robbinsdale, MN, who Vachon met for the first time in London.

Vachon won another national championship in 1949, and then, on February 7, 1950, at the age of 20, he captured the gold medal in freestyle wrestling at 174 pounds at the 1950 British Empire games (now Commonwealth Games) in Auckland, New Zealand. He loved amateur wrestling, but retired at that time, long before he would have hit his physical prime, because he was broke and there was no money in amateur wrestling.

Payette was already well known as a bouncer in Montreal when he went to the Olympics, and Vachon followed in his footsteps.

He was making $500 to $600 a week in the early 50s as a doorman at the most popular clubs in town, which was huge money in those days. Over the next few years, Vachon became something of a local legend in the city.

“He was some street fighter,” remembered Brito, who first met Vachon more than 60 years ago when he saw him compete in amateur wrestling. “Older people here remember him when he fought in the streets.”

His reputation grew when he beat the hell out of a famous professional boxer. He wasn’t a big man. And in those days with a nice pretty face, a full head of thick curly hair, was clean-shaven, almost looking like a model, he didn’t look anything like the ferocious creature of the future named Mad Dog Vachon. Since had a name all over town, a lot of tough guys in town wanted to try him on. He hurt a lot of people and never lost a fight. He was never in serious trouble because he never started a fight. One time the police warned him about using excessive force, but when it came out how the guy who he had beaten up badly, and then went to the police to press charges, had started the fight and had earlier beaten up two police officers, they let him go with just a warning. He was considered the toughest guy in town when Armand Courville, a former pro wrestler who had become the right hand man of Montreal’s mafia boss, Vic Cotroni, told him that he had beaten up too many people, and somebody was going to come after him with a knife or a gun.

Vachon had been a pro wrestling fan since childhood, going to matches to see the likes of Henri DeGlane and Jumping Joe Savoldi. But even with his background as an Olympian and a reputation in Montreal as a street fighter, local promoter Eddie Quinn didn’t want to use him, perhaps for fear he’d be too hard to handle, given his reputation around town. And at the time, the top babyface spots were locked in the promotion.

He and Payette both tried to parlay their reputations as both Olympic wrestlers and street fighters into pro wrestling. Vachon had something, although as a small, good looking babyface, he didn’t stand out or make any money. Payette, terribly shy, just wasn’t cut out for pro wrestling and didn’t last long.

Vachon only had a few prelim matches in the city when he started in 1951. He worked as a bouncer most of the year, but during the summer, would work in Northern Ontario for a summer seasonal territory run by Larry Kasabooski of North Bay. Promoter Eddie Quinn didn’t want to use him, but he did have a match in 1954 at the Forum in Montreal with Johnny Rougeau, who was the man handpicked by Yvon Robert to be the city’s next babyface superstar.

He headed to Texas in 1955 to work for promoter Morris Sigel. After three months in the territory, he and fellow Quebec wrestler Pierre LaSalle captured the Texas tag team titles from Rito Romero & Pepe Mendietta.

Paul Vachon followed in his brothers’ footsteps as an amateur. In 1955, he placed second in the Canadian nationals in the 191 pound weight class. Much bigger than Mad Dog, at 6-foot-2 ½, he grew to be close to 300 pounds. After Mad Dog found out his brother had done so well while still a teenager, he told him he should immediately turn pro. He started as a Russian, Nicolai Zolotoff, gaining experience on his own before the first big run of the Vachon Brothers in Western Canada.

In 1959, Maurice & Paul Vachon moved to Calgary to work for Stu Hart. Their gimmick was that they were two tough and crazy guys from the lumberjack camps of Quebec. For older fans it should be noted the gimmick of being the tough lumberjacks, with two brothers, one huge and one small, that was later used in Quebec and around the United States by the LeDuc brothers, who were actually not real brothers.

The early 70s feud between the Vachon brothers and the LeDuc brothers is remembered by many older fans as the hottest feud ever in Quebec, setting box office records, some of which still stand today, in a number of cities during the heyday of Grand Prix Wrestling.

“They worked here from January to July 1959,” noted Stampede wrestling historian Bob Leonard. “They had a long feud with George & Sandy Scott and shorter runs against Chet Wallick & Chico Garcia (The Atomic Blonds), Mighty Ursus & Shag Thomas and Bill & Dan Miller. Some single bouts too, including Maurice against Jersey Joe Walcott (the world heavyweight boxing champion in 1950-51, winning it from Ezzard Charles and losing to Rocky Marciano) in boxing matches.”

Paul was just starting out at the time and Maurice made the rules. The two lived in downtown Calgary, but they would train with Stu Hart, who lived more than four miles away. Maurice refused to drive, and they would always jog there, even in the freezing winter. On a cold day arrive at Stu’s house covered in frost and snow. Maurice didn’t care whether it was 25 below zero or not when they could avoid the weather and simply drive to Hart’s house. Paul did not have the same kind of mindset.

“They came in in full heel mode and really tore the place up from the get-go. In Regina and Saskatoon, we had a couple of refs, Joe Lesperance and Keith Megson, who had done some semi-pro work and didn’t mind taking the odd bump. They were about the only two on the loop who would go along with whatever happened. Maurice, after a DQ or a wild brawl, would fire one or the other, and sometimes both, over the top rope for a huge pop.”

One of the all-time classic stories of the Stampede Wrestling territory came that year. There was a well known character in Montreal named The Great Antonio, a 6-foot-6, 450-pound strongman who resembled a caveman or like a giant Rasputin come to life. He had some celebrity status in Montreal as the giant homeless guy that everyone knew with a beard so long that he’d tie it in knots on the bottom and use it as a golf club. He was already in the Guinness Book of World Records at this time for pulling buses. A few years later, Antonio appeared as a guest of Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. He later became a famous character with older fans in Japan for pulling buses as a promotional stunt, which at the time got a ton of mainstream interest, making him a big drawing card, as well as his matches with Rikidozan and Antonio Inoki, both of which turned into shoots.

The Vachons talked Stu Hart into giving him a job as a wrestler. He was a slob, who smelled horrible, lacked even the most basic of social graces, and spoke very little English.

It was known in wrestling as the “Mabel rib” (which also tells you the origin of Nelson Frazier’s ring name in the Men on a Mission days), a Western Canadian special. It was something actually played on a number of newcomers to the territory over the years. But the story with Maurice Vachon, Dave Ruhl and The Great Antonio was perhaps the greatest of all.

The story started when Antonio arrived and wrestlers would talk about this woman who lived just outside of town. It was always noted she was not the classic ring rat, but a married, high class woman whose husband was a pilot that was out of town. She was talked about as being hot, loved sex, particularly with big pro wrestlers and she was fantastic in bed. They, in fact, had a hot woman who played the part.

Ruhl, one of the biggest stars of the territory, called Antonio, pretending to be a woman, talking about how she had seen him and loved his body. Ruhl told Antonio to come to her place on a Saturday afternoon when her husband was out of town, and that she had two friends who wanted to meet Maurice Vachon and Dave Ruhl, so to bring them with him, and also bring plenty of liquor. Antonio nearly ruined it because he was insistent on going alone, but finally agreed to come with the other two.

As the hot woman lured Antonio into her bed, a man showed up, with a gun, saying he was her husband who got back into town early. The “husband” aimed the gun at Antonio, but Vachon jumped in the way to protect him. The man shot off the gun. Vachon went down like he was shot, and was covered in pre-packaged blood, looking like he was bleeding to death. Vachon, seemingly about to die, told Antonio to get away and run as fast as he could. The “husband,” still holding the gun, screamed he was going to kill him. Before he could get out, the “husband” also “shot” Ruhl and vowed to hunt Antonio down. Antonio, running as fast as a 450 pound man could, got out of the house, and in trying to get away, cut himself on the barbed wire fence. Then, after he was gone, all the people in on the prank drank Antonio’s liquor, and eventually went home.

Usually the prank ended there. But Antonio, in wandering around town, found the police station. By this point, he was completely wild-eyed and disheveled, which really wasn’t that different from how he was normally. He told the police that a man was looking to kill him and he didn’t want to leave the police station, because he feared the man would find him and shoot him, since he’d presumably already shot and may have killed his mentor, Maurice Vachon. The police came to Maurice’s apartment to tell his wife that he had been shot and may have been killed . Mrs. Vachon brought the officers into the apartment and told them that couldn’t be the case. As they came in, Maurice was in a big armchair, drinking beer, watching a hockey game, claiming to have no idea what was going on.

The police left. Eventually they figured out what happened and weren’t thrilled with that at all. Ruhl ended up charged with public mischief and had to pay a fine.

When it came to Antonio, while Vachon himself would rib him, he was still protective of the naive giant.

Gorgeous George, in the latter days of his career, old and drinking heavily, was brought in, and he was constantly putting Antonio down for being a slob and smelling so badly. After three days of this, while in Saskatoon, after a show was over and the crowd had gone home, before the wrestlers got ready for their trip back home, Maurice requested that all of the wrestlers go to the ring. Coming from Maurice, it wasn’t a request anyone was allowed to decline. With everyone there, Vachon told George that he had two choices. He would either fight Antonio in the ring, or he could choose option No. 2, which was to fight him. George tried every way to get out of it, but finally agreed to fight Antonio. They had a brief skirmish which ended quickly.

The Vachons went to Texas as a tag team, and then to the Carolinas, holding the tag team titles in both promotions. The brothers went their separate ways, as Maurice headed to work in Honolulu for Ed Francis’ thriving promotion in paradise. It wasn’t the biggest money in wrestling, but it was one of the plum jobs, working three nights a week, and living on the beach of Waikiki for months at a time.

His more famous look came, while working in Hawaii and losing a hair vs. hair match with local star Neff Maiava in the main event of the October 25, 1961, show at the Honolulu Civic Auditorium. While in Hawaii, Oregon promoter Don Owen went there on vacation, saw him work, liked what he saw and offered him a full-time run as his top heel.

Mad Dog Vachon, with the trademark bald head and goatee, and the missing teeth, was born in 1962, when he started out in the Pacific Northwest.

“During a match I went outside the ring and started to turn everything upside down,” Vachon said. “A policeman tried to stop me, and I hit him, too.”

Backstage, after the match, Owen told him that he looked like a mad dog out there. The name, one of the great ones in wrestling history, stuck. Owen wanted to create the idea of this uncivilized wildman, so billed him as being from Algiers, Algeria, which became his billed home town in many circuits for the bulk of the rest of his career.

Aside from a quick trip back home over the summer of 1963, Vachon remained based out of Oregon, where he was one of the biggest stars and best drawing cards they had ever had, garnering a reputation as a major singles star. He won the Pacific Northwest title four times, until he headed to Nebraska.

Wrestling for promoter Joe Dusek, he was brought in to be the same successful headliner he had been in Oregon. He went on a long unbeaten streak. He’s also remembered by fans in that part of the country as perhaps the biggest star and most memorable character of that era in Nebraska.

His first run climaxed by beating Verne Gagne on May 2, 1964, in Omaha, to win the AWA world heavyweight title.

In those days, Nebraska was part of the AWA, but a separate full-time circuit. They would frequently do AWA title changes in Omaha that were quickies, for a week or two, and only recognized in the state of Nebraska. During that two week period, Gagne would continue to defend the title in the big AWA circuit. They’d quicky get things back to normal, usually on the following show in Omaha. Two weeks later, Gagne returned to hand Vachon his first loss and regain the title.

But Gagne was evidently impressed by what he experienced, because he brought Vachon to the main circuit a few weeks later. On October 20, 1964, Vachon beat Gagne in Minneapolis and this time was recognized everywhere as the AWA champion, making him one of the biggest stars in the business as one of pro wrestling’s big four world champions along with Lou Thesz (NWA), Bruno Sammartino (WWWF) and Cowboy Bob Ellis (WWA).

During his first reign as champion, he defeated the likes of Pat O’Connor, Billy Red Cloud, Yukon Moose Cholak, Pampero Firpo, Reggie Parks, Ivan Kalmikoff, The Mongolian Stomper, Blackjack Lanza, Don Jardine, Mighty Igor Vodik, Wilbur Snyder, Dick the Bruiser, Danny Hodge and The Crusher. While still holding the AWA title, he returned to Oregon and actually held the Pacific Northwest title and AWA title at the same time. As AWA champion, he actually lost to Stan Stasiak in both Portland and Seattle on his way out in his short run.

He lost the AWA title to Crusher on August 21, 1965, in St. Paul, but regained it on November 12, 1965, in Denver. A big match during this run came on February 26, 1966, in Chicago, where Vachon faced WWA champion Dick the Bruiser, in a unification match. This was not the same WWA title that was considered one of the big four at the time. That WWA title was based in Los Angeles and recognized in Japan as well. Bruiser had gone to Los Angeles and won that title. Then, prior to a match at the Olympic Auditorium with Destroyer in 1964, Ellis had attacked Bruiser, causing him to lose via count out. Destroyer won the WWA title, and Bruiser returned home to Indianapolis, claiming he was still WWA champion and that became Indiana’s version of the world title for the next two decades. It became the only WWA title in 1968, when the Los Angeles office rejoined the NWA.

Since the AWA title was more prestigious, Vachon went over in the Chicago unification match, winning via count out. But the title change wasn’t acknowledged in Indiana, where Bruiser ran the promotion and continued to defend the title. Vachon was billed as the unified champion in Chicago until he lost the AWA title one year later to Gagne, at which point it was just called the AWA title and the WWA title was never talked about on Chicago shows.

Another notable match came on January 2, 1967, in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, where Vachon wrestled Bruno Sammartino. What made this match historically significant is you had the AWA champion facing the WWWF champion on an NWA show. It wasn’t a unification match, as in this instance, Vachon was not billed as a champion. It was only billed in Toronto as Sammartino defending his title, in a match Sammartino won.

While still holding the AWA title, he went to Atlanta on January 13, 1967, to team with Paul Vachon to beat Alberto & Enrique Torres to win their version of the world tag team title.

While he had some main events a few years earlier on trips to Montreal, his first run as a top singles headliner came due to his reputation garnered in Oregon and the AWA as a money drawing champion.

Remaining AWA champion, he beat Hans Schmidt in Chicoutimi, Quebec, on January 24, 1967, to win the Montreal version of the International title. He had to win the AWA title and hold it for several years before he could return home and truly be recognized as a superstar. During 1967, he drew the largest crowd of the year at a time when wrestling was not in a hot period in the province, drawing 12,000 fans for a match at the Forum in Montreal where he teamed with Sweet Daddy Siki against Johnny Rougeau & Carpentier.

The Vachon Brothers lost the Georgia version of the world tag titles back to Enrique & Ramon Torres on February 3, 1967. Vachon then dropped the AWA title to Gagne in St. Paul on February 26, 1967. During this period, he was working four different circuits, Georgia, Quebec, AWA and Nebraska.

During what was recognized throughout the AWA as his second and longest title run, he defended his title against Tim Woods, Stan Pulaski (Eric Pomeroy, who in Georgia became his brother, Stan Vachon), Crusher, Igor, Snyder, Parks, Mr. Wrestling (Woods under a mask, and Vachon actually helped come up with the idea for Woods to don the white mask and call himself Mr. Wrestling, as masked babyfaces on top were a rarity in those days), Gagne, O’Connor, Billy Red Cloud, Chris Markoff, Bruiser, Bobby Managoff, Haru Sasaki, Luke Brown, Ernie Ladd, Killer Kowalski, Ron Reed (Buddy Colt), Dale Lewis, Carlos Colon and Grizzly Smith.

“Here was a guy who was a horrible worker, and no matter who you were, you had to adapt to his style, and you never knew what the hell he was going to do,” said Bill Watts in the book “Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels,”“But did Mad Dog draw money? You’re damn right he drew money. Why’d he draw money if he was such a bad worker? He drew money because of the intensity of who he was. His interviews were so dominant because he believed that he was the toughest son of a bitch that walked. And he may have been.”

“It wasn’t that tough to work with him, but you had to be careful,” said Brito. “One time I worked with him at the Paul Suave Arena. He hit me over the head with a camera. I needed 20 stitches on the top of my head. Sometimes he got carried away. But I used to love to work with him. He made it believable for the fans. He didn’t work stiff. But he wasn’t loose either. But he you to grab and fight for what you wanted, you know what I mean? That’s why the fans bought it. He wasn’t the greatest. He didn’t do all that fancy stuff, but the people believed in him. When people believed in him, 5-foot-6 ½ inch Mad Dog Vachon could wrestle 6-foot-6 ½ inch Killer Kowalski, and the people believed he could beat the shit out of Kowalski, and he could. “

He returned to Quebec for a full-time run in May, 1967. While in Minneapolis, he met a kindred spirit, a tall, balding, shy amateur wrestler named James Raschke from Omaha. Raschke wasn’t doing well as a pro wrestler. Vachon met him in Minneapolis, looked at him, and told him he’d make a good German. He gave him his break in 1967, bringing him to Montreal to be his tag team partner, Baron Fritz Von Raschke.

“He had all the instincts and was one of the greatest professional wrestlers of all-time,” said Raschke.

On August 14, 1967, he defeated Johnny Rougeau to win the International title, but it was a short run. Nine days later, Vachon was in a serious auto accident, breaking his pelvis, and he was out of action for five months.

After the accident, he came to a show in Montreal and told fans that he would be back, and stronger than ever.

Before his debut in Japan, he spent a few weeks in California. He was considered such a big name that in his big show debut, on August 23, 1968, at the Olympic Auditorium, he pinned Mil Mascaras. This earned him a title shot at WWA champion Bobo Brazil two weeks later, which he lost via DQ.

His first Japan tour was September 20, 1968, to November 16, 1968. He was booked as a major star, going to a double count out with Kintaro Oki and beating Antonio Inoki via count out in single matches. On October 4, at Korakuen Hall, Vachon & Killer Karl Kox won a non-title match over International tag team champions Giant Baba & Inoki, then the unbeatable dream team. He lost via DQ in his first and only singles match with Baba in Japan, held in Nagasaki. His biggest match was October 24, 1968, in Hiroshima, where Baba & Inoki retained their titles beating Vachon & Kox in 31:25 when Inoki rolled up Vachon in the third fall. Baba & Inoki also beat them in a rematch five days later in Nagoya.

The big tag team run of Mad Dog & Butcher Vachon in the AWA started at the beginning of 1969. During that period, with AWA champion Gagne wrestling a very limited schedule, it was the Vachons on top who carried the territory from the heel side, during the strongest period up to that point in the history of the promotion. They rarely lost, and when they did it was mostly via DQ, except against their hottest rivals, the Flying Redheads of Red Bastien & Billy “Red” Lyons.

The Vachons finally captured the AWA tag titles from Dick the Bruiser & The Crusher on August 30, 1969, at the International Ampitheatre in Chicago, before more than 10,000 fans, in a match where the story was that Crusher injured his leg.

They headlined during that period mostly against Lyons & Bastien, who were considered by many as the best working babyface tag team in the country at the time. Among the other teams they worked with were Watts & Snyder, O’Connor & Snyder, Watts & Man Mountain Mike, Carpentier & Snyder, Bruiser & Moose Cholak, Watts & Carpentier, Crusher & Carpentier, Gagne & Crusher, Pepper Gomez & Carpentier, Gomez & Crusher, Ladd & Snyder, Ladd & Brazil, Crusher & Igor, fellow heels Lars Anderson & Larry Hennig, heels Nick Bockwinkel & Lanza, giants Plowboy Stan Frazier & Tex McKenzie, Bastien & Gomez, Bastien & Hercules Cortez, Gagne & Haystacks Calhoun and Crusher & Bull Bullinski.

The biggest business was in 1970, coming off one of the legendary angles in AWA history. It started at the January 17, 1970, TV tapings of All-Star Wrestling in Minneapolis. The Vachons were facing Carpentier & jobber Bruce Kirk. They had destroyed Kirk and were double-teaming Carpentier, when Crusher came out to make the save. In the ensuing brawl, Crusher rammed Mad Dog’s head into the ringpost. Vachon went to the ground to blade his forehead, and accidentally, Crusher stomped on the back of Vachon’s head on the floor, causing the blade to go in too deep, which caused him to cut an artery.

The blood spurted out of Vachon’s head. Vachon’s blood got all over the curtains of the TV studio, and they were nearly banned from the building. Both fans, and some of the TV stations that aired the footage complained to the promotion about the violence. Rodger Kent, doing the announcing, went completely out of character, screaming for help, saying that Mad Dog was bleeding to death and somebody needed to get him a pressure bandage. Vachon needed dozens of stitches, with the number growing as time went on. But the out-of-control chaos was memorable, and led to the most famous run of the Crusher vs. Mad Dog feud.

The feud drew record business throughout the AWA. A week later, in Crusher’s home town of Milwaukee, they drew 12,000 fans at the Arena, at the time the city’s indoor record. A cage match on the next show at the St. Paul Civic Center drew 10,048 fans. Tag title matches with the Vachons vs. Carpentier & Crusher were doing big business everywhere. The most famous match, on June 13, 1970, a singles cage match at the Milwaukee Arena, drew 12,076 fans paying $58,270, setting the all-time Wisconsin gate record. For decades, this was the single most remembered wrestling match in the city, largely because as Vachon was beating down on Crusher, a middle-aged woman hopped the rail and started climbing the cage to try and save Crusher.

On a television talk show after Crusher passed away in 2005, it was said that even at that time, even 35 years later, you could go into any bar in Milwaukee and bring up wrestling, and the conversation would inevitably lead to the bloodbath at the Arena where the old lady tried to climb the cage.

On August 14, 1970, at Comiskey Park in Chicago, a cage match where the Vachons retained the tag team titles winning two of three falls from Bruiser & Crusher drew 21,000 fans paying $148,000, the largest wrestling crowd in the world that year and, at the time, the largest pro wrestling gate ever in the United States.

In early 1971, they went to Japan as champions for the IWE, retaining their titles over Great Kusatsu & Thunder Sugiyama twice. Before going, they stopped in Portland on February 23, 1971, and lost the titles to Kurt & Karl Von Steiger, in a title change only recognized in Oregon. Then they went to Honolulu the next day, where they got a win in defending their titles over Gagne & Billy Robinson (this was before Robinson was in the AWA as he was a star in Hawaii first) when Mad Dog pinned Gagne in the third fall. Then, after Japan, Gagne beat Mad Dog to keep the AWA title on March 14, 1971, n Honolulu. They went back to Portland on March 16, 1971, to beat the Von Steigers via DQ in a match where the title could change hands that way, and retained them, winning via DQ in a rematch two nights later in Salem, and end that tag title story in Oregon.

The big run ended on May 15, 1971, in Milwaukee, when they dropped the titles to Bastien & Cortez, largely because the Vachons were returning to Montreal to buy into the newly-formed Grand Prix Wrestling promotion.

“Butcher did pretty good on that run, but even he would say he was riding on Maurice’s coat tails,” said Brito. “In Quebec, he never made it big like Maurice.”

Before his biggest run in Quebec, Mad Dog went back to Hawaii for a few months. Lonnie Mayne, who he had worked with a few years earlier in Oregon, had emulated Vachon, going to Hawaii as Mad Dog Mayne (in 1973, Vince McMahon Sr. would later change him to Moondog Mayne, which was where wrestling’s Moondog tradition got started). So it was natural to do the battle of the Mad Dogs.

To this day in Montreal, the early 70s, with the war between International Wrestling and Grand Prix Wrestling is considered the golden age of pro wrestling in the city. Perhaps the most remembered feud of that era was the Vachons vs. The LeDucs.

Due to disorganization and egos, Grand Prix was splitting into two factions, with the big shows being on the same night, in Sherbrooke and Verdun. There were two cliques in the promotion, the Vachon clique and the Carpentier clique. The Vachons vs. LeDucs were used as the headliners in Sherbrooke.

Mad Dog started doing promos saying he knew dirty little secrets about the LeDuc Brothers, who had gotten over like gangbusters in International Wrestling, were given a big raise to jump sides and do the natural brother feud. Mad Dog said that the two were not really brothers (they weren’t), and that Paul LeDuc’s wife was a thief. Paul LeDuc did strong interviews back, saying that he wanted everyone with a criminal record to come down to Sherbrooke and watch Mad Dog get beat up really bad. They sold out several weeks in a row.

In Montreal, Paul Vachon was the listed promoter. Of the key partners in the promotion, Maurice, Carpentier and Paul Vachon, because the Montreal Athletic Commission had a rule that the promoter couldn’t wrestle, Paul was considered the least important in the ring of the three, so he had the promoters license, and also he was the most suited to actually run the business.

At that point, they brought in Kowalski to be Mad Dog’s partner against the LeDucs. But in their first meeting, in Sherbrooke, so many chairs were thrown and Kowalski said, “I don’t need to put up with this shit,” and went back to the locker room.

The Vachons vs. LeDucs was actually biggest in Quebec City, where a July 31, 1972, match set the city’s all-time attendance record with 15,000 fans. A rematch, two weeks later, drew 17,008 fans, which to this day is the city’s all-time record.

During the match, Paul Vachon was injured, meaning both babyface LeDucs were facing Mad Dog.

“The crowd started to take Maurice in pity and took his side,” remembered Paul LeDuc about the unplanned double-turn. “They turned Maurice babyface in that match. Maurice was telling us to keep gong, but Jos didn’t like it since he thought Maurice was stealing the babyface reaction.”

On September 15, 1972, a singles match between the stars of each team, Maurice vs. Jos, drew 15,000 fans in Quebec City, but the fans took Mad Dog’s side, which infuriated Jos.

During 1972, Mad Dog and Carpentier had a strong singles feud over the Grand Prix title at the Forum in Montreal. Mad Dog won the title on April 7, 1972, drawing 12,878 fans, and Carpentier regained it on June 28, 1972, drawing 12,894 fans.

The Boxing Day show card, the day after Christmas, at the Forum, drew 14,896 fans as Bruno Sammartino & Gino Brito & Dino Bravo beat Vachon & Kowalski & Don Leo Jonathan.

The plan was to build for the biggest matches ever, when the weather got better, in the summer of 1973, at Jarry Park, the home of the Montreal Expos. But before they got there, the LeDucs jumped back to work for the Rougeaus and International Wrestling. After they left, the new babyface Vachon Brothers worked against both faces and heels, with their big rivals being The Hollywood Blonds, Dale (Buddy) Roberts & Jerry Brown, managed by Sir Oliver Humperdink.

“I worked for both sides,” said Brito, who said Grand Prix Wrestling was very much like WCW Nitro a quarter-century later. “I worked for Grand Prix. Let me tell you, you never knew one day to the next what you’d be doing. They had their cliques, the two Vachons on one side and Carpentier, Lucien Gregroire and Yvon Robert Jr. (who inherited his stock when Yvon Robert, who helped start the promotion, died of a heart attack) on the other. You knew that sooner or later, they would fall. Johnny Rougeau kept a low key approach, kept his expenses down, and that’s why he won at the end. You could see how much Grand Prix was spending and you knew it would close down. They were a flash in the pan. But they were very big for a while.

“They had no direction, but what saved them was The Giant (Jean Ferre, later Andre the Giant) was new, Don Leo Jonathan was brought in They brought Kowalski back. They had good talent. They had the Indians, The LeDucs, the Vachons, but they didn’t know how to hold it together. In those days, my dad was alive. He told me that if they can last three years, then I know nothing about the business.”

“I remember in Rimouski and Ottawa, there was a riot and let me tell you, Maurice could handle a riot pretty good,” said Don Leo Jonathan, whose feud with Ferre in the battle of the giants was one of the other major programs of the glory years. “I was involved, too, but I was lucky to have Maurice with me. He was a good guy to have your back. Me and him go back a lot of years. I don’t remember the first time I met him. It seems like he was always there. In the days of Grand Prix, as far as I was concerned, you never knew he was one of the bosses.”

“I’m losing one of my good friends today,” he said this past week.

Grand Prix Wrestling lasted right at three years, but right before they collapsed, they put on the biggest wrestling show in the history of the city.

The climactic Mad Dog vs. Jos LeDuc match was gone when LeDuc thought Mad Dog was stealing his babyface reaction in the match in Quebec City, leading to him leaving the promotion.

Instead, the now-babyface Vachon was to headline against Montreal’s most successful heel in its history, Kowalski. Most credit the record crowd to Vachon’s promos leading up to the match. The first big one was vowing in a voice that made you convinced he would really do such a thing, that he would rip Kowalski’s ear off. Even though it was 21 years earlier, in 1952, the single most famous incident in the history of Montreal wrestling, at least until the Bret Hart vs. Shawn Michaels match in 1997, was when Kowalski delivered a kneedrop off the top rope, which ended up slicing the cauliflowered ear off the head of Yukon Eric. A rematch in early 1953 at the Montreal Forum was the first live pro wrestling broadcast that went nationwide on Canadian television, and because of that, was still the most remembered match to many of the older fans of that era. In a second interview, Vachon, playing off the death of Eric, a huge area star who shot himself in 1965, vowed that if he couldn’t beat Kowalski, he would commit suicide. Obviously something of this nature could never be done today, but because of the nature of the complete promo, and the delivery, they not only got away with it, but it worked.

On July 14, 1973, a crowd of 29,173 fans packed Jarry Park. It was a complete sellout, the largest crowd for any event in the stadium, the largest pro wrestling crowd in the world of 1973, the largest North American gate up to that time in history, and was the largest pro wrestling crowd in Canada until Hulk Hogan and Paul Orndorff broke the record in Toronto in 1986. It is still the biggest crowd for a pro wrestling match ever in Montreal. Given his promise, and that he was the babyface, Vachon won the match. The headline in the newspaper the next morning read,“Mad Dog Vachon beats Kowalski before nearly 30,000 fans, and will not commit suicide.”

Part two of our look at Mad Dog Vachon will be in next week’s issue

***************************************************************

MAURICE “MAD DOG” VACHON CAREER TITLE HISTORY

AWA WORLD HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Verne Gagne May 2, 1964 Omaha; lost to Verne Gagne May 16, 1964 Omaha (title changes only recognized in Nebraska); def. Verne Gagne October 20, 1964 Minneapolis; lost to Mighty Igor Vodik May 15, 1965 Omaha; def. Mighty Igor Vodik May 22, 1965 Omaha (title changes only recognized in Nebraska); lost to The Crusher August 21, 1965 St. Paul; def. The Crusher November 12, 1965 Denver; title held up vs. Tim Woods January 8, 1966 Omaha; def. Tim Woods January 14, 1966 Omaha (title changes only recognized in Nebraska); lost to Dick the Bruiser November 12, 1966 Omaha; def. Dick the Bruiser November 19, 1966 Omaha (title changes only recognized in Nebraska); lost to Verne Gagne February 26, 1967 St. Paul

AWA WORLD TAG TEAM: w/Paul Butcher Vachon def. The Crusher & Dick the Bruiser August 30, 1969 Chicago; lost to Kurt & Karl Von Steiner February 23, 1971 Portland, OR; w/Paul Butcher Vachon def. Kurt & Karl Von Steiger March 16, 1971 Portland, OR (title changes only recognized in Oregon, the Vachons were defending the titles in Honolulu and Japan during the interim); lost to Red Bastien & Hercules Cortez May 15, 1971 Milwaukee; w/Verne Gagne def. Ray Stevens & Pat Patterson June 6, 1979 Winnipeg; lost to Jesse Ventura & Adrian Adonis via forfeit when Gagne misses July 20, 1980 match in Denver

IWA WORLD HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Mighty Inoue April 10, 1975 Tokyo; lost to Rusher Kimura April 19, 1975 Sapporo

IWA WORLD TAG TEAM: w/Ivan Koloff def. Strong Kobayashi & Great Kusatsu April 18, 1973 Ibaragi; lost to Rusher Kimura & Great Kusatsu May 14, 1973 Funabashi

IWA INTERNATIONAL HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Hans Schmidt January 24, 1967 Chicoutimi, Quebec; lost to Johnny Rougeau June 5, 1967 Montreal; def. Johnny Rougeau August 14, 1967 Montreal; title vacated when injured in an auto accident August 23, 1967

INTERNATIONAL TAG TEAM: w/Edouard Carpentier def. The Scorpions February 1978; no record of them losing the title

GRAND PRIX WRESTLING WORLD HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Edouard Carpentier April 7, 1972; lost to Edouard Carpentier June 28, 1972; def Edouard Carpentier May 7, 1973 Quebec City; lost to Edouard Carpentier June 27, 1973 Montreal

GRAND PRIX WRESTLING WORLD TAG TEAM: w/Paul Butcher Vachon held titles 1971; lost to Dale Roberts (Buddy Roberts) & Jerry Brown October 1972; w/Killer Kowalski def. Jos & Paul LeDuc 1972; lost to Jos & Paul LeDuc 1973

WWA WORLD HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Dick the Bruiser February 26, 1966, Chicago; title change only recognized in Chicago and not in other WWA cities and eventually WWA title was never talked about in Chicago going forward

NWA TEXAS TAG TEAM: w/Pierre LaSalle def. Rito Romero & Pepe Mendietta April 1955; lost to Larry Chene & Raul Zapata May 10, 1955 Austin; w/Paul Vachon def. Ciclon Negro & Torbellino Blanco November 8, 1960 Dallas; lost to Ciclon Negro & Torbellino Blanco November 15, 1960 Dallas; w/Duke Keomuka beat Ciclon Negro & Torbellino Blanco December 1960; lost to Sputnik & Jet Monroe January 1, 1961 Fort Worth

NWA TEXAS BRASS KNUX: def. Superstar Billy Graham May 2, 1975 Houston; lost to Superstar Billy Graham August 5, 1975 Dallas

NWA INTERNATIONAL TAG TEAM: w/Paul Vachon def. George & Sandy Scott January 30, 1959 Calgary; lost to Shag Thomas & Mighty Ursus (Jesse Ortega) March 27, 1959 Calgary; w/Paul Vachon def. Chico Garcia & Chet Wallick April 16, 1959 Regina; lost to George & Sandy Scott May 1, 1959 Calgary

NWA WESTERN CANADIAN OPEN TAG TEAM: w/Paul Vachon def. Chico Garcia & Chet Wallick February 17, 1959 Edmonton; lost to Shag Thomas & Mighty Ursus March 10, 1959 Edmonton; w/Paul Vachon def. Charro Azteca & Chet Wallick May 12, 1959 Edmonton; Titles vacated

NWA WORLD TAG TEAM (Georgia): w/Paul Butcher Vachon def. Enrique & Ramon Torres January 13, 1967 Atlanta; lost to Enrique & Ramon Torres February 3, 1967 Atlanta

NWA SOUTHERN TAG TEAM: w/Paul Vachon def. Jack Curtis & Ray Villmer January 9, 1961 Charlotte; lost to Sandy Scott & George Becker March 27, 1961 Charlotte

NWA PACIFIC NORTHWEST HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Luther Lindsay October 4, 1962 Portland; lost to Herb Freeman January 26, 1963 Portland; def. Herb Freeman February 16, 1963 Portland; lost to Herb Freeman May 10, 1963 Portland; def. Herb Freeman May 17, 1963 Portland; lost to Billy White Wolf (Adnan Al-Kaissie) June 5, 1963 Portland; def. Nick Bockwinkel November 21, 1963 Portland; lost to The Destroyer (Dick Beyer) January 3, 1964 Portland; def. Pepper Martin June 5, 1965 Portland; lost to Stan Stasiak June 18, 1965 Portland; def. Lonnie Mayne May 30, 1968 Portland; lost to Lonnie Mayne June 6, 1968 Portland

NWA PACIFIC NORTHWEST TAG TEAM: w/Fritz Von Goering def. Luther Lindsay & Shag Thomas September 21, 1962; lost to Luther Lindsay & Shag Thomas December 9, 1962

NWA NORTH AMERICAN TAG TEAM: w/Baron Von Raschke def. Black Gordman & Great Goliath September 30, 1976 Kansas City; lost to Mike George & Super Intern (Tom Andrews) October 21, 1976 Kansas City

AWA NEBRASKA HEAVYWEIGHT: def. Ernie Dusek March 28, 1964 Omaha; lost to Otto Von Krupp (Professor Boris Malenko) August 15, 1964 Omaha; def. Otto Von Krupp August 22, 1964 Omaha; lost to Billy Red Cloud October 9, 1964 Omaha

AWA NEBRASKA TAG TEAM: w/Haru Sasaki won title August 14, 1965; lost to Verne Gagne & Tex McKenzie September 4, 1965 Omaha; w/Haru Sasaki def. Verne Gagne & Tex McKenzie September 18, 1965 Omaha; Title vacated when Vachon won AWA world heavyweight title

AWA MIDWEST TAG TEAM: w/Bob Orton Sr. def. Reggie Parks & Doug Gilbert March 15, 1968 Omaha; lost to Reggie Parks & Doug Gilbert March 22, 1968 Omaha; w/Bob Orton Sr. def. Reggie Parks & Doug Gilbert April 1968; lost to Stan Pulaski & Dale Lewis April 1968; w/Paul Butcher Vachon def. Woody Farmer & Reggie Parks January 11, 1969 Omaha; lost to Stan Pulaski & Chris Tolos January 25, 1969 Omaha

WRESTLING OBSERVER HALL OF FAME (1996)

GEORGE TRAGOS/LOU THESZ PRO WRESTLING HALL OF FAME (2003)

PRO WRESTLING HALL OF FAME (2004)

WWE HALL OF FAME (2010)

Mad Dog Vachon obituary

Moderator: Dux

-

T200

Topic author - Sergeant Commanding

- Posts: 5434

- Joined: Mon Sep 15, 2008 1:38 am

- Location: House of Fire

Mad Dog Vachon obituary

From the Wrestling Observer:

-

WildGorillaMan

- Sergeant Commanding

- Posts: 9951

- Joined: Wed Jan 07, 2009 9:01 pm

Re: Mad Dog Vachon obituary

Pour one out on the curb. PBUH

Re: Mad Dog Vachon obituary

holy shit nobody's reading that wall of text

"Know that! & Know it deep you fucking loser!"

Re: Mad Dog Vachon obituary

The guy who writes that is some damn historian/writer.

"There is only one God, and he doesn't dress like that". - - Captain America

-

Holland Oates

- Lifetime IGer

- Posts: 14137

- Joined: Thu Feb 07, 2008 8:32 am

- Location: GAWD'S Country

- Contact:

Re: Mad Dog Vachon obituary

RIP

Gawddamn they don't cut any corners at the observer.

Gawddamn they don't cut any corners at the observer.

Southern Hospitality Is Aggressive Hospitality

-

T200

Topic author - Sergeant Commanding

- Posts: 5434

- Joined: Mon Sep 15, 2008 1:38 am

- Location: House of Fire

Re: Mad Dog Vachon obituary

Part 2

James Raschke, a shy former member of the University of Nebraska and later U.S. national wrestling team, makes no bones about the fact he owes his long career as Baron Von Raschke to his friend of 47 years, the late Maurice “Mad Dog” Vachon.

“When I was breaking into the business, Verne Gagne broke me in, and I was working setting up the rings and refereeing, I first met Mad Dog. I didn’t know him. It was at the Director’s booth at the TV station (in Minneapolis in 1966, where AWA All-Star Wrestling was taped). I helped set up the ring and was told to watch the matches like a rookie, which I was at the time. I set up the ring and watched, in a dark room, in the hallway, I heard a voice, I didn’t even know who it was at first, and he said, `You’d make a great German,’ in his Mad Dog voice.”’

The next two or three tapings, whenever Vachon would see Raschke, he’d pause, say the same words, “You’d make a great German,” and walk away. Vachon didn’t even know Raschke was of German heritage, nor that Raschke actually studied German while in college.

Finally, at a show, the two were formally introduced. They got along because of their similar backgrounds. Raschke placed third in the 1963 world championships in Greco-Roman wrestling in the heavyweight division, the best finish any American had ever had in the world championships in Greco-Roman wrestling in any weight class up to that point in time. He was considered as having a shot at being the first Olympic Greco-Roman medalist in U.S. history, but suffered an injury that year, and couldn’t compete. It wouldn’t be until 1984 that an American medaled in Greco-Roman. Raschke got a job as a school teacher, which didn’t pay much. Verne Gagne then tried to recruit him to be a pro wrestler.

“Before I met him (Vachon), Verne took me to my first pro wrestling matches,” he said. “I’d only seen pro wrestling once or twice in my life. I wasn’t interested in pro wrestling growing up. He took me to an outdoor show at the baseball stadium in St. Paul. The main event was Mad Dog Vachon against The Crusher (most likely an August 21, 1965 show at Midway Stadium where Crusher pinned Vachon to win the AWA title). I’d heard both of their names. I’d never met Crusher. They got in the ring. I was in the first couple of rows. I watched them and I was impressed. I was a longtime amateur wrestler, and even boxed a little bit. I was amazed with what I saw, how close they worked. It looked like they were killing each other. And they probably were.”

Then Raschke agreed to break in. Gagne trained him and started him at the bottom, working on the ring crew.

“He was already a big star and we started talking, and got friendly,” said Raschke. “After a while, he asked me if I wanted to be his tag team partner in the Montreal territory. Jack Britton (the father of Gino Brito) and the Rougeaus (Johnny and Jacques Sr.) owned it. I said, `Sure.’ I didn’t know any better. I was only a rookie. He said once again in his Mad Dog voice, `You’d make a good German. We’ll call you Baron Fritz Von Pumpkin.’ I said, `Let me think about that.’”

Raschke, only a few months in the business, talked to Wally Karbo, Gagne’s co-promoter, who told him Vachon probably got the idea from a wrestler who was a major star in Oregon when Vachon became a major star a few years earlier, Kurt Von Poppenheim. Raschke, even with his limited knowledge of wrestling, didn’t think Fritz Von Pumpkin was the greatest heat getting name, thinking he’d come out and people would laugh at him, which was not what he was looking for. He told Vachon that his own last name was a nice German name.

“I had just gotten married and we took everything we owned, which was our two rubber tree plants and all our clothes, and we went to Montreal from Minneapolis,” he said. “When we got there, Mad Dog and I went the first Monday to the Paul Suave Arena in Downtown Montreal. I had a singles match that night with Larry Moquin, an old-timer, a seasoned veteran. Larry made me look really good. This was my first night as Baron Fritz Von Raschke. My wife’s girlfriend had made me a short cape out of red and black material and off I went. The people booed and hissed, so I reacted. I got a lot of heat. Later, Dog and I came out for an interview. I didn’t even know we were going to a place where French was the main language. I said a few things in broken German with an accent, but I wasn’t too sure of myself. Mad Dog was always a great interview.

“The next week, we were a tag team. He got all this heat. Everyone knew him from years gone by. I got it by being associated with him. He was short and handsome. I was tall and handsome,” Raschke joked. “He was teaching me all the time. I learned so much wrestling with him as a partner. He was my friend, my mentor, my guide for my first eight, nine, ten months in the business.”

Raschke quickly learned Vachon’s reputation in Montreal.

“You didn’t want to cross him. He was a very tough man, a tough street guy. We were a tag team. I don’t want to exaggerate. But almost every night he wrestled, especially if we wrestled Carpentier and Johnny Rougeau, our matches seemed to end in a riot. I was so new. I didn’t even know what was happening. He’d let the heat build up. Then it would explode. We had to fight our way back to the dressing room so many times.”

One night, they had a cage match scheduled against the Rougeau Brothers, Jacques Sr. & Johnny. The fans were so rabid that they tore down the cage before the match even started.

“The cage was lying on the floor,” he said. “So this time, we actually had to fight just to get to the ring, and when it was over, we had to fight our way back. He was always the lead guy in the fight.

“He’d clear the way and would tell me, `Don’t go down, because if you go down, you’re done.’ He liked getting that kind of heat.”

The tag team, which was reprised years later in separate runs in the AWA and later the Central States, ended the first time when Vachon suffered a broken pelvis in an auto accident at the time he was International heavyweight champion. Trying to keep the territory strong with Vachon gone as top heel, the promotion brought in The Sheik to carry the title. But Sheik had his own territory and was in demand all over the world, so by November 1967, Von Raschke, barely a year in the business, was champion in one of the strongest wrestling territories in the world at the time.

“I was on my own, but all his heat carried over to me,” Raschke said. “The territory kept blossoming. It made me, to where I could get booked almost anywhere I wanted after that.”

Bobby Heenan noted that working with Vachon were some of the most physical matches of his career. He said Vachon’s fists were like little shovels, and because of the storylines and character portrayals, the times Vachon actually got a hold of Heenan, he had to give him a beating. Heenan said Vachon would take him down in the corner and repeatedly punch him to the body and it felt like he was being hit with a weapon with every blow.

Once, they were in a match that went outside a building that was next to the train tracks. Vachon took him outside, and pinned him down on the tracks and was beating on him, Heenan asked quietly, “When do I get up?”

“When you hear the train,” said Vachon.

Dick “Destroyer” Beyer, who first wrestled Vachon in a main event when it was babyface Dick Beyer against Maurice Vachon in the main event at the Honolulu Civic Auditorium in 1962, remembered late in both men’s career having a battle in Montreal.

“The Mad Dog says to me, `We got to give them a barn burner here,’” Beyer said to In Your Head radio. “They expect that we’re going to knock the hell out of each other.’ So we started out the match wrestling, and then all of a sudden it was kick, stomp, throw out of the ring. Mad Dog came out, he hit me with a chair, and out the aisle we went.”

Vachon took Destroyer into the dressing room and was pounding on him there until Beyer yelled, “Mad Dog, there’s no fans here! It’s just the boys. Let’s get the hell out in the arena.”

Vachon and Raschke remained friends throughout their careers, and long after both had retired. The two spoke just two days before Vachon’s death. They worked as a heel tag team in the mid-70s in the AWA. Vachon a few years later turned cult babyface when he and Verne Gagne went after AWA world tag team champions Pat Patterson & Ray Stevens eventually winning the titles.

The storyline there was that Gagne had tried to win the tag team title with various partners, including Billy Robinson, who had been pushed for years as the area’s best wrestler, and Crusher, its best brawler. Finally, discouraged that no matter who he chose, they could never get the job done, Gagne said he had to fight fire with fire, and get the dirtiest, nastiest wrestler in the business and his biggest career rival, and brought in Vachon as his partner. With Gagne, time always stood still, so even though Vachon was a few months before his 50th birthday, and Gagne was a few years older, in the AWA, they were still portrayed in 1979 as they were in 1966 when they were the big singles stars.

Von Raschke’s babyface turn came after the AWA had shot an injury angle where Jerry Blackwell & John Studd had put Vachon out of action. Von Raschke, while wrestling in Florida, cut his first babyface promo, vowing revenge for his mentor.

“Something happened to Mad Dog, he was gone from the wrestling scene for a while,” said Raschke. “I got this call, Wally (Karbo) called and said, `We want you to come back and be Mad Dog’s avenger. I did an interview for that. It got over. While he was injured, I don’t remember if it was a work or shoot, but he was living in Winnipeg and got a job in the gold mines in the Northern territory. They flew him in and bused him to the mines. It was so cold they had to shuttle him to the mines. It was terribly cold, ice. He called me and said, `Baron, it’s dark, cold, quiet and it’s beautiful.’ He worked in the mines and everyone recognized him. Everyone knew he was Mad Dog, so everyone there thought he was a spy for the company.”

When he returned, he claimed that when he was injured, he got a job working in the gold mines in the Northern territory to get himself back in shape for wrestling. He said it was cold and dark and he suffered, reaching new lows, until he hit rock bottom, and at that point he realized he had to come back and get back at Blackwell and Studd.

Vachon was a wildman when he was young. A lot of wrestlers found him difficult to work with. He mixed in technical wrestling with his brawling into the early 60s. But by the time he got to the AWA and became one of the biggest stars in the business with his world title reigns, he was in pure Mad Dog mode.

Along with The Crusher and Gagne, they built the AWA territory into what many considered to be among the best territories to work. The money was good, as regulars could earn $45,000 to $75,000 per year, which in the 60s was very good money. They worked 15 to 18 shows per month, with the schedule slowing down in the summer so they could enjoy the hunting, fishing or other hobbies. The idea was to run less often because the idea was that the people had other things to do. Also, Crusher, the top star, would frequently get into fights with Verne Gagne on money, some would joke, like clockwork, just before the summer. He’d quit, go home, and then they’d make up in the fall. There were also downsides, like traveling long distances by car in horrible weather. Still, in the late 70s, when Jack Adkisson (Fritz Von Erich) suggested to AWA champion Nick Bockwinkel that he could get him a run with the NWA world title, a position that paid significantly better, Bockwinkel presumed more than double of what he was earning, Bockwinkel still turned it down because he liked the lifestyle he was leading.

Vachon was a regular until 1971, when he and his brother dropped the tag team titles to help open up Grand Prix Wrestling. But he was always used as a special attraction, sometimes as a de facto babyface as the guy being brought into town to face the new top heels, and other times back in his familiar heel role. One major program in 1973 was Crusher calling on his arch enemy, Mad Dog, to face his new big nemesis, Superstar Billy Graham & Ivan Koloff. After Graham, with help from Koloff, did the unthinkable, and beat Crusher in a singles match (Crusher hated to lose and almost never did anywhere in that era, let alone in Milwaukee), a tag team cage match set the city’s all-time gate record, breaking the mark Crusher had set with Mad Dog in their legendary 1970 match.

In 1974, ABC’s Wide World of Sports agreed to televise pro wrestling on network TV for the first time in nearly two decades. The segment on the show that dominated Saturday afternoon television during that era, was built around an early match of 420-pound Chris Taylor, a star off the 1972 Olympics, where he won a bronze medal. Taylor was early in his career. Gagne put Vachon in as Taylor’s opponent. It was something to see the legendary Jim McKay call a pro wrestling match. Taylor was limited and Mad Dog only did his usual act. It wasn’t much of a match. McKay noted that it was real blood coming out of Taylor’s nose as Vachon roughed him up, but that “he’s really not choking him over the ropes,” as Vachon was doing and refused to stop when a DQ was called.

Later, Taylor got his revenge, as he threw out Vachon when he and Ken Patera, both off the Olympic team, were the two survivors in winning a two-ring Battle Royal, which sold out the International Ampitheatre in Chicago. It was one of only two network broadcasts of wrestling in the 70s, the other being in 1976 when Muhammad Ali did matches in Chicago against Kenny Jay and Buddy Wolff, prior to his closed-circuit match with Antonio Inoki.

Once Gagne called him to be his tag team partner against Patterson & Stevens, Vachon was a babyface from that point on. The AWA was doing well, but really exploded from 1981 to 1983 with Hulk Hogan as the top star. Vachon, in his 50s, was kept off wrestling on television, with only clips of his arena matches shown. He did little in the ring. Sometimes it was sad because when doing the piledriver, the move he made famous in the territory in the 60s, he would struggle just to get his opponent up, and nearly lose them.

There was a story from that era that became famous in wrestling lore. Vachon, on Gagne’s small plane that the main event wrestlers would travel in, at one point opened up the door of the plane while flying, which forced an emergency landing.

Raschke believes that somebody slipped Vachon a pill, as he would have never done such a thing on his own. Vachon threw one of the wrestlers’ bags out the door laughing at the idea it was going to crash somewhere in the middle of nowhere.

Raschke said he wasn’t on the plane, but noted that it’s a famous story among wrestlers of that era, and that he’s talked to several who were in the plane, but everyone gave him a different story as to what happened.

“I’ve probably heard the story 50 times, but it’s been told 50 different ways. It’s like Ray Stevens said, `What good is a story like that if you can’t embellish it?’”

Gagne, who was also not on the plane, was furious and read him the riot act. He was screaming at Vachon for what he did, and told Vachon as punishment he was banning him from the plane, which would force him to make long drives in the car to get around the territory. When he was done, Vachon responded, when talking about his next booking “So Verne, what time does the plane leave?”

Perhaps his most memorable promo, which was not the usual market-specific promo, but a one-take job where Vachon was in his workshop with a hammer and other tools, constructing a coffin for Blackwell that he vowed to put him in. The promo played in every AWA city, and in most cities, multiple times. Part of its effectiveness was the way Blackwell sold it on his own interviews afer it would play. The idea was actually something from Vachon’s past, as he did a similar promo building a coffin for Lonnie Mayne when they were feuding in Oregon, and built to drawing what at the time was the biggest crowd ever in Oregon for wrestling in the late 60s at the peak of that feud, where Mayne ended up putting Vachon in the coffin.

“Mad Dog was probably the consummate interview guy,” said Mean Gene Okerlund on In Your Head radio, who handled the interviews for the AWA during the Vachon babyface era. “Whether it was behind the cage or it was in a workshop trying to construct a coffin, or whatever it happened to be, he was a classic in every sense of the word. I think what everybody has said about him is what it is. He was kind of a favorite of mine and I think he was a favorite of the boys in the locker room. Certainly, even though the fans at one time or another probably hated him vehemently, he ended up being kind of the guy they loved to hate.”

Even well into his 50s, in the core AWA cities, Vachon was still over like a major main eventer, and often headlined in front of big crowds when Hogan was wrestling in Japan. In cities like Winnipeg, where he lived for years, Milwaukee, because of the feud with Crusher, and Montreal, he was a name that everyone recognized instantly, whether or not they even watched wrestling.

But when the AWA would go into new markets, where his history wasn’t as strong, people saw him as a short, paunchy, old man who couldn’t do much. The interviews and character were more than main event level, but it was harder for fans in places where he didn’t have history to take him seriously.

Because of that, it was a miscalculation on everyone’s part when Vachon jumped to the WWF at the time they were trying to raid everyone from the AWA. In a land of younger steroid bodies, Vachon’s unique voice talking about it being “A Dog Eat Dog World,” wasn’t enough to make the new generation of fans think they were seeing the Mad Dog Vachon of 20 years earlier. When he did come back to the AWA, by then, the bloom was off the rose for both him and the promotion. He also worked some for International Wrestling out of Montreal, announcing a retirement tour throughout Quebec.

His farewell match was on October 13, 1986, where the 57-year-old Vachon teamed with long-time rival Jos LeDuc to beat Man Mountain Moore & Gilles “The Fish” Poisson, another wrestler that Vachon started out in the 60s, before 3,200 fans.

Maurice Vachon established himself very early as a drawing card. Working in Northern Ontario in a summer 1952 feud with Dory Funk Sr., the babyface pretty-boy Olympian from Quebec against the cowboy from Texas was a big hit, breaking box office records in North Bay, ONT. But in Montreal, promoter Eddie Quinn had no interest in him at first. After doing well in Texas in late 1954 and early 1955, he moved up to the semifinal level in Quebec and Ontario on good nights, although he was still a prelim wrestler in Montreal, one of North America’s strongest wrestling cities.

He captured the Texas junior heavyweight title in late 1956, his first singles title, losing to Luis Martinez on February 6, 1957, in Corpus Christi. Vachon & Joe Christie won a match over Mike DiBiase & Bulldog Danny Plechas for what was called the toughest tag team trophy, which they started to defend, before losing a barbed wire match in Corpus Christi on March 13, 1957, to Martinez & Pepper Gomez. But when he returned to Quebec that summer, he was back in prelims.

His first true run as a headliner would have been in 1959 while working for Stu Hart, forming a tag team with brother Paul. He even got a shot at world champion Pat O’Connor on February 26, 1959, in Regina. On July 14, 1959, also in Regina, before 4,000 fans, he was knocked out in a boxing match against former world heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott who Stu Hart brought in for Stampede week.

He wrestled much of 1960 in Texas, including being in what was billed as the first South American style tag team match, on October 4, 1960, at the Dallas Sportatorium. The rules were that the only way to win was to win three consecutive falls. The heel team of Vachon & Don Leo Jonathan & Danny McShain & Haru Sasaki beat Torbellino Blanco & Ciclon Negro & Mr. Kleem & Silento Rodriguez in a match that went nearly a dozen falls. It drew so well that they brought it back in Dallas two weeks later as Maurice & Paul Vachon teamed with Jonathan & McShain to beat Blanco & Negro & Rodriguez & Jesse Cardenas. While there, he talked Don Owen into giving a job for a fellow Montreal wrestler whose career was struggling named Pierre Clermont, who came in as Pat Patterson. It was Patterson’s success in Oregon as a worker that opened the door for him to go to San Francisco, where he became the tag team partner of Ray Stevens. Patterson always stated, like Von Raschke, that he owed his career to Vachon, and told people that no matter what, he would never fully be able to pay back the debt.

It was Patterson who came up with the spot where Diesel (Kevin Nash) used Vachon’s prosthetic leg on Shawn Michaels, taking it off him, in their April 28, 1996, WWF title match PPV main event, as a way of getting Vachon a payoff at that stage of his life.

On May 31, 1998, in Milwaukee, Patterson got Vachon another PPV payoff. Announcer Michael Cole got in the ring to pay tribute to Vachon and Crusher, sitting together nearly three decades after the most famous match in the history of the city. Cole gave both an appreciation plaque while Jerry Lawler, who was then still doing a heel role, complained about how the segment was a waste of time. Lawler got in the ring and started making cracks about how old and washed up the two were, and once again, took off Vachon’s prosthetic leg. Crusher saved Vachon. Lawler actually went for the leg a second time, and got it off, but Crusher attacked Lawler, got it back, and hit Lawler with it. The segment was far sadder to watch than it read because of how slow moving Crusher, 71 at the time, had gotten by that point in time, and how bad it looked for Lawler to sell for him.

When he heard that Vachon’s memory was fading, Patterson pushed hard to get Vachon inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2010. Seven years earlier, when Vachon was given the Mike Mazurki Award at the Cauliflower Alley banquet in Las Vegas, and accepted it with a speech that may still be the single greatest promo I’ve ever seen. However, the next several years were not kind to Vachon, whose memory had faded badly by the time of this both induction, and his induction in 2009 into the Quebec Sports Hall of Fame.

Vachon’s run in Oregon had a number of highlights, including a big drawing feud with Haystacks Calhoun, and as the top star, business was strong enough that they were running live shows in Portland at the Armory twice a week.

Vachon’s debut in Minneapolis, on July 9, 1963, at the Auditorium, was less than memorable. Before a near sellout crowd that saw Crusher, with help from Dick the Bruiser, beat Gagne, via count out, to win the AWA title, Maurice Vachon worked the second match of the show, losing to Don McClarity. It was just a one-shot deal, driving from Oregon back to Montreal, where he worked the summer of 1963. He was still Maurice Vachon back home, and worked in the middle of the cards.

After returning to Oregon to finish 1963, he moved to Omaha at the start of 1964 for promoter Joe Dusek. On January 3, 1964, he dropped the Pacific Northwest title to The Destroyer at the Portland Armory. The next day, he debuted at the Omaha Civic Auditorium in a prelim match beating Maurice LaPointe, the first place outside of Oregon that he was Mad Dog Vachon.

By May 2, 1964, Vachon beat Gagne in Omaha before 6,025 fans, the largest crowd of the year, to win the AWA title, in a title switch only recognized in Nebraska. Gagne won it back two weeks later before 5,520 fans. Two weeks later, Gagne brought him to Minneapolis, this time as Mad Dog Vachon, beating Billy Goelz in a mid-card match. By October 20, 1964, he beat Gagne for the fully recognized AWA title in Minneapolis before 3,979 fans. Crowds immediately picked up to 5,000 to 7,000 fans for Vachon’s title defenses until he lost to Gagne via DQ before a sellout of 9,109 on Thanksgiving night. The whole territory was up in 1965, particularly when Vachon was matched with Bruiser, Crusher or Gagne, including sellouts on April 17, 1965, and June 26, 1965, for Minneapolis title matches with Gagne.

Vachon regained the title on November 12, 1965, in Denver, before 4,000 fans, setting up a rematch with Crusher on the Thanksgiving show on November 25, 1965, which drew a near sellout 8,116 fans.

Omaha was down, but Vachon came up with an idea. Vachon had worked on top in title matches with Tim Woods. Vachon was always a big fan of guys with legitimate amateur backgrounds, and suggested that Woods remake himself as Mr. Wrestling, with a white mask. In that era, masked men were always heels. But Mr. Wrestling in Omaha and later Georgia, where he became an even bigger star, was there to represent the purest in technical wrestling and skill.

For the January 8, 1966, show in Omaha, Mr. Wrestling promised he would take off his mask and win the AWA title from Vachon. He unmasked before the match, revealing himself as Tim Woods, and then won the title, but his feet were on the ropes for leverage. A week later, the local Omaha World Record reported that AWA President Stanley Blackburn had reviewed the match and evidence showed Woods with his feet on the ropes while scoring the fall, so the result was overturned to a no contest, and a rematch was ordered. Vachon “regained” the title in a match that went 60:00, with Vachon winning the first fall, and going on his bicycle and stalling out the rest of the match.

Vachon’s idea, done on a bigger scale, led to the first sellout of pro wrestling ever at the Omni in Atlanta. On June 1, 1973, new NWA world champion Harley Race came in, a week after winning the title from Dory Funk Jr. Mr. Wrestling vowed to unmask before the match started, reveal his identity, and then win the title. He revealed himself as Tim Woods, and then went 60:00 before 16,500 fans, holding a sleeper hold on as time expired. Race was asleep, but it was ruled the bell rang to end the match before the ref ruled Race went out, in a photo finish.

While he had headlined in other cities in Quebec years earlier, the first record of a Mad Dog Vachon main event in his home town of Montreal wasn’t until December 5, 1966, when Vachon & Hans Schmidt faced Edouard Carpentier & Johnny Rougeau. By 1967 he was the territory’s top heel and champion, regularly teaming with Von Raschke.

After suffering a broken pelvis in August of that year, he was out of action until January, when he returned to the AWA. That summer, he returned to Oregon, and his feud with Mayne was so hot that their biggest match, on July 9, 1968, was moved to the Memorial Coliseum and drew more than 10,000 fans. He went to Southern California before a Japan tour, and was only in the territory a few weeks. After beating Mil Mascaras at the Olympic Auditorium, the September 6, 1968, match where Bobo Brazil retained his WWA title over Vachon, who was disqualified for biting, drew a sellout reported at more than 11,000.

In 1969, after matches where AWA tag team champions Bruiser & Crusher did crowds of 9,512 and 8,708 in Milwaukee against The Vachons, they did the title switch to the Vachons in Chicago before 10,000 fans at the Ampitheatre on August 30, 1969.

The territory picked up, largely because the Vachons could draw as tag champs on a regular basis. Bruiser & Crusher were big draws whenever they teamed. But with Bruiser owning the Indianapolis promotion, it was hard to get a lot of dates on him for the AWA territory. The big program for the rest of 1969 was a successful title program with the Vachons vs. The Flying Redheads, Billy “Red” Lyons & Red Bastien.

The AWA in 1970 was highlighted by The Crusher vs. Mad Dog feud coming off the bloodbath on television. St. Paul, Milwaukee and Winnipeg all sold out within a one week period. Denver did a near sellout, and then sold out for a Gagne & Crusher vs. Vachons match. Milwaukee, Crusher’s home city, was sellout almost every month leading to the famous cage match. Even after the cage match, the return a month later with the Vachons vs. Bruiser & Crusher drew 10,812. Comiskey Park in Chicago with the Vachons vs. Bruiser & Crusher in a cage match did 21,000 fans and set the North American all-time gate record at the time with $148,000. Denver set its record for a Crusher vs. Mad Dog cage match. Minneapolis/St. Paul was only doing average business, but the rest of the major cities were all peaking at record levels.

On May 15, 1971, in Milwaukee, in a no DQ match, Bastien & Hercules Cortez beat the Vachons before 10,271 fans to win the tag team titles. The title changed hands since the Vachons were going back to Montreal to buy into Grand Prix Wrestling.

Montreal wrestling exploded at that time, peaking with the Mad Dog vs. Killer Kowalski match at Jarry Park that set the North American gate record and Canadian attendance record with 29,127 selling the place out.